As a first-timer in Japan, I was struck particularly by the wealth of art that surrounds Kyoto. Since my arrival, I have grown to appreciate the interactions of past and present artistic traditions, which in my opinion, have only further contributed to the city’s coinage as Japan’s great cultural repository. With this said, I have realized that the national treasures of this rich, art-embedded city could not have possibly thrived today without expertise in areas of art restoration, preservation and conservation—believe it or not, there is a difference! In short, I was determined to engage in the very discipline that firstly, initiated my interest in Japanese, and secondly, brought me to Kyoto. That discipline is none other than paper conservation. While formal conservation training in Kyoto normally requires a 10 year apprenticeship, my 1 year commitment abroad did not quite make the cut. Through the help of KCJS, however, what originally seemed as an impossible CIP became possible.

This semester, I was stationed with a small restoration team at Ritsumeikan University’s Art Research Center (ARC). ARC is currently undertaking a large-scale digitalization project entailing the compilation of Japanese cultural assets into accessible archives for researchers worldwide. In effort of this project, restorations are being made on paper-based materials ranging from woodblock prints (ukiyo-e ; 浮世絵) to illustrated bound books (wahon ; 和本). Due to poor storage conditions, these pieces have been eaten by insects and/or have suffered from severe deterioration. Through hands-on training and gained experience, I have developed an awareness of materials and preservation in Japan as well as acquired the patience necessary to safely handle and perform restorations on these Edo-period treasures. Furthermore, I have been able to indulge in the fine details of wahon and ukiyo-e print illustrations, all while improving my technical Japanese skills.

On my first day at ARC, I came prepared with a notebook expecting to observe restorations in the process. To my surprise, as I walked into the project room, I was promptly handed an apron and tweezers, led to a table equipped with a light-box, and sat down in front of a page from a damaged booklet. When I heard the words “honmono” (本物) and “renshu” (練習) in the same sentence, my hands froze…I mean, if you had heard that for your first “practice session” you would be restoring a “genuine article”, wouldn’t you have also had a similar reaction?…Nevertheless, this valuable method of instruction—no matter how cliché it must sound—allowed me learn directly from my mistakes. In connection with a class fieldtrip to a sudare bamboo blind workshop earlier in the semester, each student had the chance to weave a strip of bamboo into a sudare. By engaging in the process, each student “learned by doing”, which I have realized is a firm belief held not only by craftspeople in Japan, but also by restorers.

Over the semester, I worked primarily on worm-eaten booklets analyzing damage and infilling areas of loss with fibrous washi (和紙) paper. After applying homemade nori, which is a wheat-starch based adhesive, around the outline of the hole, a pre-cut piece of washi is set into place. The moisture from the nori expands the paper fibers, so the restored area must be placed between two pieces of cardboard under an iron weight until fully dry. The result: a wrinkle-free restoration. Due to this vital step, each hole must be patched one-by-one. From my abridged explanation, the restoration process must seem rather simple; however, tedious in nature, restoration is a committed job that requires concentration and careful attention to detail. For instance, I spend roughly 10 hours patching a single page, followed by another 4 hours searching for and reattaching small pieces that had fallen off. If anything, I feel as if I am solving a puzzle, and though frustrating at times, I have found much satisfaction in the process. While I am carrying out the same procedures, every restoration requires individual attention. In addition, I have also learned related tasks including the preparation of nori paste as well as the creation of traditional koyori exposed-bindings.

Outside of the classroom, my CIP experience has given me the opportunity to observe the Japanese language in a working environment. My relationship with the other workers has improved to the point where I am addressed very informally as “Are-chan”. However, when I receive a new project or when I am asked a favor of, I am always addressed with the formal title, “sama”. Although I find this unfit for my status as a student with little experience in restoration, these formalities embedded in the language reinforce the professionalism of the workplace.

In all, I am excited to continue my CIP into next semester. With a better handle of the Japanese language I will hopefully be able to further deepen my understanding of restoration principles in Japan, and how that contrasts with the West. As the project steadily progresses, I am also looking forward to seeing how my efforts have contributed to ARC and the greater Kyoto community.

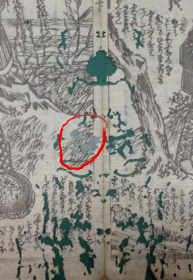

Close-up of a worm-eaten page from an illustrated booklet. Circled in red is the area of restoration. Can you tell the difference?

Miscellaneous pieces without a home…yet!

I’m so glad to hear you had such an amazing experience with your CIP after the rocky start I heard you had this semester. It truly is amazing how your genuine passion for art conservation combined with the help of KCJS allowed you to overcome the experience barrier. With that said, even though you appear to truly enjoy the activity, was it not a bit difficult for you to have to go there two times a week and for a couple hours each time?

Thank you for commenting~

If time permitted, I would have loved to go more than twice a week! After starting CIP, managing time became my biggest challenge, especially since my commute home from Ritsumeikan was nearly 1.5 hours. However, once I accepted my limitations and made compromises (which involved moving closer to campus mid-way through the semester), I was able to better handle the demands of my CIP and coursework.

I’m happy to hear that you found a CIP that’s directly related to your major and your interests! What became of that first piece that they had you working on? Did you end up finishing the restoration work yourself, or did another member of the team finish it off?

Thank you for commenting, Alan!

In the beginning I don’t recall ever working on a project to its completion. Normally I would be given a page from another member’s “project” and make a few restorations. Only after becoming more comfortable with the tools and materials did I start receiving individual projects.

That first piece has probably been sent to the photography studio by now, and is in the process of becoming apart of ARC’s digital archive!