For my CIP this semester, I took tea ceremony lessons. When I came to Japan for the first time in 2018, I had the opportunity to go to a rural high school’s tea ceremony club. Admittedly, I didn’t really like matcha at the time, so I was having a hard time drinking it then. However, between then and the start of this last semester, I’ve come to love matcha, so deciding to take tea ceremony lessons was a no-brainer for me. Our first day was more of a demonstration and less of a lesson. It was still winter at that point, so the more suburban/semi-rural area that we traveled to for the demo was even more beautiful because of the snow on the ground. The windy streets surrounded by trees and mountains were like nothing I had ever seen. When we finally found the ryokan we would have classes in, we met Fujimura Sensei. She was wearing a kimono, which fit right in with the general traditional vibe of the small tatami room where our classes would be held.

I was extremely nervous at that point. Everything in the room was so perfect, intentional, and unfamiliar to me, and I was afraid that I was somehow going to break something. Since this was very early into the semester, this had become a very common feeling since arriving in Japan: being generally uncomfortable. As Fujimura Sensei was doing the demonstration, I was so impressed by not only the intricacy of the ritual but how graceful and sure she was in each of her movements. I was a little intimidated at first, thinking there was no way I would be able to come close to that level. Even so, Fujimura Sensei was extremely kind, and I would later find out, just as patient and encouraging. Our lessons were completely in Japanese, and when I would struggle with the language, she would use hand movements to help me understand. Also, Connie Situ and Geetanjali Gandhe, the two other KCJS students who were taking the lessons with me, were beyond helpful when it came to helping me understand some of the Japanese instructions. Through their help and Sensei’s teaching style and overall friendliness, I was able to let go of the need to be perfect, and this made me so much more confident and, ultimately, have a lot more fun. This is something I want to carry with me after the end of the program because it can open more doors for me because I am less afraid of failure and am more comfortable with being uncomfortable.

My CIP was also special because Fujimura Sensei went out of her way to teach us about the cultural history of Kyoto and Japan at large. To celebrate White Day, she prepared a multiple-course meal for us and explained the meaning and traditions behind each dish. It was delicious and I was really happy to participate in this holiday for the first time. Later in the semester during sakura season, we did an ochakai, or formal tea ceremony, at Heian Jingu, and later drove out to the countryside to do our own tea ceremony. It was such a beautiful experience, and I’m grateful to Fujimura Sensei for putting it all together. This semester was definitely full of awkward moments and small failures, but because of that, I feel like I am a more confident person than I was at the start.

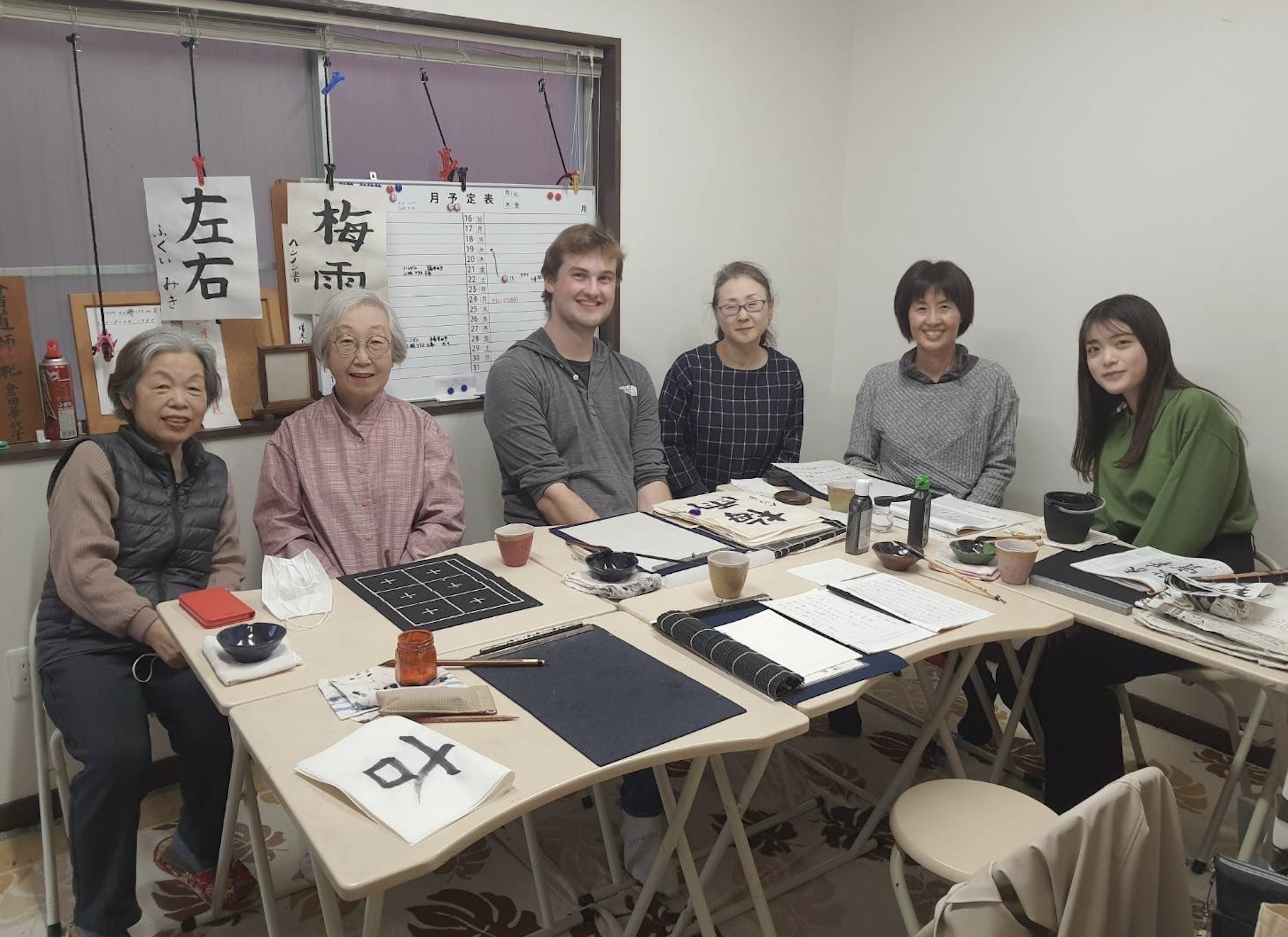

This semester, I studied a form of traditional decorative papermaking known as karakami with Sugawara Fumiha, a karakami artisan based in Kyoto. Professor Melissa Rinne, who I took the class Kyoto Artisans and their Worlds with, connected me to Sugawara-sensei, who graciously offered to work with me for my CIP.

This semester, I studied a form of traditional decorative papermaking known as karakami with Sugawara Fumiha, a karakami artisan based in Kyoto. Professor Melissa Rinne, who I took the class Kyoto Artisans and their Worlds with, connected me to Sugawara-sensei, who graciously offered to work with me for my CIP.

For my CIP I took tea ceremony, or sadou, lessons with Fujimura Sensei. The KCJS office introduced us to Fujimura Sensei and it seems like KCJS has a long relationship with her. While normally the study of sadou takes decades and is a very lengthy process, since we only had one semester Fujimura sensei customized the lessons for us so that we were able to end by being able to perform the tea ceremonies, or the obon-temae. The tea room is a little out of the way in Takagamine, but the environment is absolutely stunning and so the commute is worth it. The tea room is situated right over a river in a silent forest, so you can hear the sound of the water while in the tea room. Sensei is an extremely elegant woman who is also one of the most precious and sweetest people I have ever met. She even made a bento for us on two occasions, for the Doll Festival and cherry blossom viewing, and of course we got to enjoy the most exquisite wagashi, or seasonal Japanese confectionary every class. The thing that was the most meaningful for me was that in every lesson sensei would also make a point to talk about how to use the philosophy that sadou teaches us and incorporate it into our busy, stressful everyday lives.

For my CIP I took tea ceremony, or sadou, lessons with Fujimura Sensei. The KCJS office introduced us to Fujimura Sensei and it seems like KCJS has a long relationship with her. While normally the study of sadou takes decades and is a very lengthy process, since we only had one semester Fujimura sensei customized the lessons for us so that we were able to end by being able to perform the tea ceremonies, or the obon-temae. The tea room is a little out of the way in Takagamine, but the environment is absolutely stunning and so the commute is worth it. The tea room is situated right over a river in a silent forest, so you can hear the sound of the water while in the tea room. Sensei is an extremely elegant woman who is also one of the most precious and sweetest people I have ever met. She even made a bento for us on two occasions, for the Doll Festival and cherry blossom viewing, and of course we got to enjoy the most exquisite wagashi, or seasonal Japanese confectionary every class. The thing that was the most meaningful for me was that in every lesson sensei would also make a point to talk about how to use the philosophy that sadou teaches us and incorporate it into our busy, stressful everyday lives.