KCJS Fall 2011

Community Involvement Project, Blog Entry 2

The photograph on my desktop “beneath” the empty white and mocking blue of the word processor shows Mount Fuji flanked in the foreground by the foothills of the Minami Alps. I had gotten up at 4 in the morning, packed away my frozen tent, and stumbled sleepily to the summit of Kita Dake in time to take it just as the sun came up. Looking at it helps me to escape, in some sense, the confines of my room when work pins me to my desk, although in terms of air temperature my room and the second highest peak of Japan at sunrise in late fall are not such different places (and I’m wearing the same cozy socks now as I was then). This brings me closer to the point of this exposition: to reflect on my experiences in the Doshisha Alpine Club. That trip was not, in fact, one of the club’s, but it may as well have been. If Doshisha University’s fall break was aligned with that if my study abroad program, perhaps it could have been.

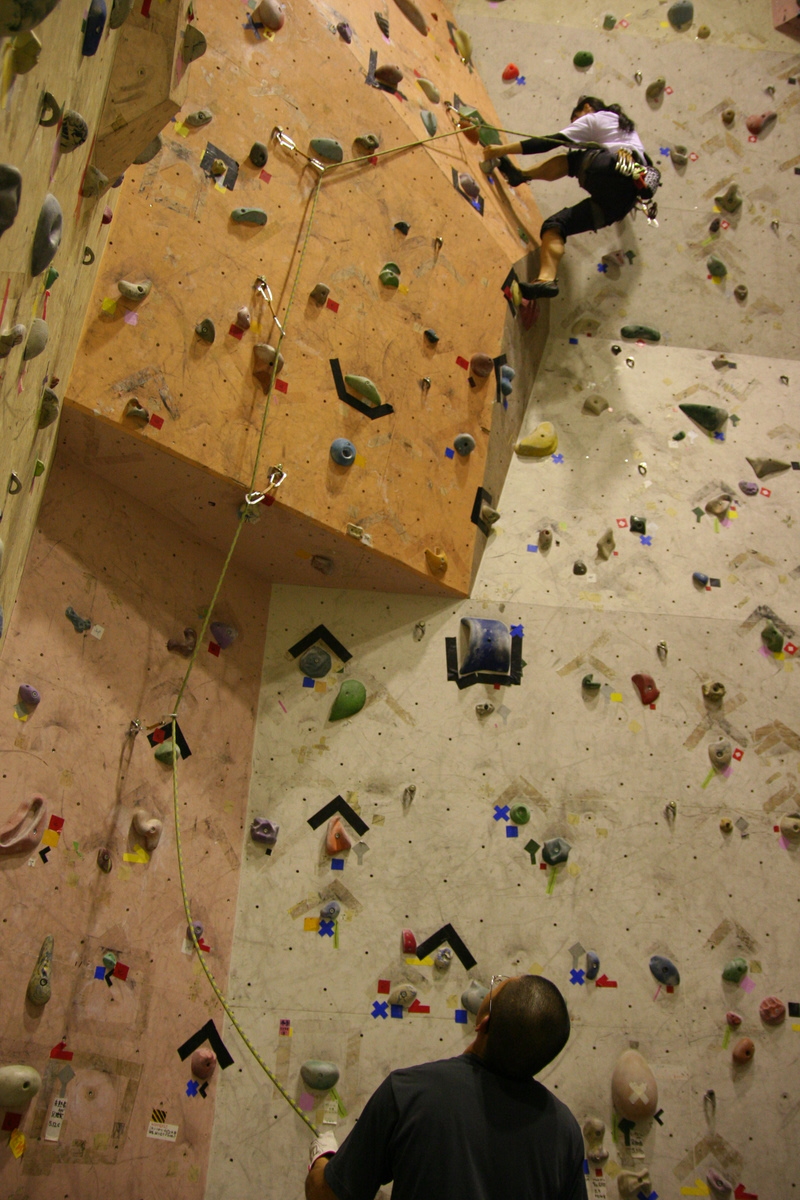

Every Thursday for the past ten weeks, I have commuted by train to practice rock climbing with two other members of the Doshisha Alpine club. A number of factors have conspired to prevent me from participating as much as I might like to: the commute is long enough that I can’t really afford to go more than once a week, my Japanese doesn’t allow me to say simple but important things like “don’t put your weight on the rope yet or you’ll fall to your death, I haven’t finished the anchor” or to understand the same, and because I’m not a true Doshisha student I don’t have the insurance policy I need to participate in outdoor activities. So I haven’t been attending the weekend alpine climbing training sessions that this club holds in place of the drinking sessions that I hear comprise the weekend itineraries of other clubs, nor will I go on their winter climbing expeditions next week. Incidentally, that expedition doesn’t line up with my vacation time either, and miscommunications in 100km/hr ice-laced winds are bad enough even when everybody speaks the same language.

In spite of these obstacles and the condition of quasi-membership they impose, I’m going to miss the two people I rock climb with every Thursday, and I think to some extent they’ll miss me. One might think that the fact that every Thursday we trust each other’s belay to prevent lethal (or paralyzing, or maiming…) falls has brought us together, but we exercised this trust without much thought from the very first day, and the first few sessions had a rather awkward and formal social character, so I don’t think this has much influence. My relationship with the two other Thursday-afternoon-rock-climbing-practitioners has progressed in the same manner as an ordinary friendship, with common interests and shared activities doing battle with an exceptionally stiff language barrier. I humbly assume all responsibility for communication failures while in Japan, but the other person’s speed has a tremendous influence and I can still hardly understand anything my climbing partner says. It’s a testament to the strength of unspoken communication that we’ve come to understand something about each other’s character without ever really hearing any of each other’s ideas.

Is this alpine club here in Japan different from the one at Cornell? Well, Cornell University is located a solid 6 hour plane ride away from anything I would call “alpine”, so we don’t have an alpine club in the true sense of the word, but we do have a university funded outdoor club that offers PE courses in everything from canoeing to ice climbing. The more I think about their official structure and composition, the less I can justify drawing comparisons between the two institutions, but ultimately they both represent groups of people who spend time together outside. The senpai-kohai relationships evident in the speech patterns of Japanese club members struck me at first as evidence of the presence of a hierarchy completely absent in the American club model. Ultimately, beyond dictating which verb-forms are appropriate for whom, and fostering self-introductions that include what this American student finds to be an awkward and unnecessary mention of what year student what is, these relationships don’t seem to have too much influence. So I suppose an alpine club is an alpine club, Japan or America (unless it isn’t).

I’ve gotten somewhere, or at least consumed some of that taunting white space. Now I’ll press save, put away this awful blue, and go back to gazing at the sea of clouds to which Fuji is an island, a distant perfect lonely cone of rock.