For my CIP project, I decided to join my host sister in learning calligraphy.

The classroom is found at the top floor in a building next to the local train station. Students ranged from elementary school children to people well over their 50 years. Although Sensei individually teaches students at their respective level, the students of all ages and levels interact. In such a way, the newer students can be inspired by seeing someone else to produce a beautiful piece, and the older students can be reminded of how pure and fresh raw calligraphy can be.

Classes consist of sensei demonstrating how to draw a character in Shodo (Cursive) Style and I copying it several times-usually until I get the hang of it. Starting Calligraphy, I didn’t think it would be too hard, we are just writing, right…but it actually takes a lot of practice. During my first lesson, I was eager to begin, but Sensei kept telling me to go slower as I write my characters. In order to carefully define the strokes: the ink must be allowed to sink into the paper before continuing, which required slower movements.

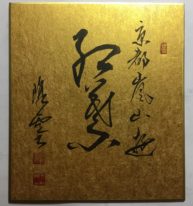

Before the fall break, Sensei gave me a calligraphy gift. It was written on a small gold-painted wooden board. In the middle it had the characters for Red leaves:紅葉 and surrounding it were characters that I had learned how to read and write in Shodo style. Such as Arashiyama嵐山, Bamboo竹, and to spend time pleasantly: 遊ぶ . The gift was personalized, and made me appreciate it so much more. During one of our conversations, the topic of nature and seasons came up, and I learned that Autumn was his favorite. I purchased some tea over my fall break, specifically an autumn flavor, as an omiyage for him. I was really happy to see his reaction as he received it. Gift giving culture and appreciation for the seasons is real in Japan!

Learning calligraphy is like learning a different set of Kanji, some of them don’t look anything like the print version, but learning a traditional art or craft can really give you a different perspective, and you realize that these arts are still very present in Japan’s Pop Culture.