For my CIP, I have been studying the Japanese art of Sumi-e– paintings done with Sumi ink and a calligraphy brush– in a small-group lesson with a Kyoto woman. Fujiwara Sensei is trained in Chinese ink painting but has been working in the Japanese style for the last decade. She hosts the lessons from her studio, which she shares with her husband who runs a kimono printing workshop upstairs.

When I attend the class most Wednesdays, I find myself in a circle of two to five older women who are extremely friendly, funny and talkative. None of them take the class or their painting hobby too seriously, yet most of them are incredibly talented. They use a combination of the black Sumi ink and pigmented watercolors to create vivid, professional-looking pieces. It’s so valuable to me, as an amateur artist who is new to the Sumi-e style, to have these Sempai classmates’ skill to aspire to. Fujiwara Sensei, of course, is a master of the art–not just when creating her own pieces, but even when assessing others’ work for its design or technique.

Calligraphy brushes (fude) and ink stone (Sumi), the only two tools needed to create Sumi-e paintings. Just add water. (Image taken from http://www.juanaalmaguer.com/)

There is much more technical training involved in learning Sumi-e than I had expected going into the classes. As with any of the Japanese “ways”–Sadou (tea ceremony), Shodou (calligraphy), and so on–there is a particular way to go about Sumi painting that does not leave much room for free interpretation. I think that as I grow as a Sumi-e artist I would like to be able to change some of these traditional standards in my own art, in order to create something that is individual and unique to the times and to my own ideas, but before I put my own spin on the ancient art, I must really master the techniques that my Sensei is teaching me now.The first thing I was taught, starting on the first day of class, was the vocabulary of terms central to the art. Particularly important are the names of the three elements necessary to every “complete” Sumi-e painting, each of which refers to a different way of combining the brush, ink, and water to create part of a picture. These terms are especially interesting to me because their dictionary meaning is very simple, but their connotation in the Sumi-e world is infinitely important. For example, “nou-dan” literally means “light-dark,” but it refers to the vital gradient between light and dark that is used in good Sumi-e work.

The other two main brushwork elements are “nuzume”–to spread or bleed–and “kassure”–to graze. A piece without all three of these features is considered to lack true atmosphere or flow; it merely depicts objects without showing their relationship to one another.

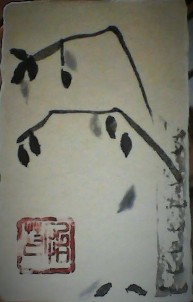

See the example below, which is a fall Sakura tree that I painted last week. The leaves together create the “nou-dan” gradient, while the trunk is an example of “kassure”. In order to incorporate “nuzume,” I added the blurry falling leaf to the right.

I am still working on mastering these techniques, as well as the art in itself of layout and composition, but Fujiwara Sensei has been very helpful in that process and I am pleased with the work I’ve done so far. I am also glad that I have had so many chances to practice conversing in Japanese with the Sensei and my older classmates, on a wide range of topics from our artwork to our families to aspects of Japanese culture and tradition.