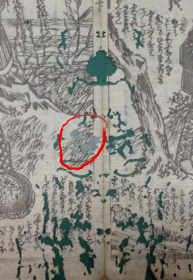

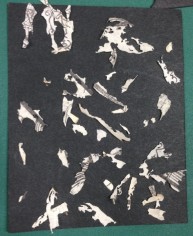

Over two semesters at KCJS, I have been training with a paper restoration team at the Ritsumeikan University Art Research Center (ARC). At ARC, I work mainly with damaged Japanese bound books dating to the Edo period. In most cases I encounter books containing full-page illustrations devoured by worms and beetles. Therefore, when beginning a new project, the severity of the damage is first evaluated and then, based on the amount of surface loss, a suitable treatment is decided on. The standard methods used to mend these areas of loss are known as infilling (tsukuroi) and back-lining (urauchi). Both methods serve different purposes, but are similar in the way that washi paper, sympathetic in thickness and tone of the damaged paper, is adhered with starch paste (nori) to treat the loss.

While incredibly valuable, the technical skills I have acquired only describe a single side of my experience at ARC. Twice a week, as I continue to practice my techniques, I also engage in a facet of the Japanese work community. As expected, this has led to quite a few interesting cultural and language exchanges. First of all, the restoration team consists of a total of three people, all middle-aged women. Everyone is on a different working schedule, so when I go to ARC I am usually working alongside Nakamura-san, the head of the restoration team.

When I first began training at ARC, the most challenging barrier I faced was communication. I was afraid to hold conversations and I struggled to understand the directions that I was being told, even when heavily aided by Google translate. This semester, however, it is undeniable that living in Kyoto has improved my ear for both standard Japanese and “Kansai-ben”, the local dialect, and has opened up new opportunities to be more interactive within ARC. For instance, being able to better communicate with the team has helped me understand in greater depth the reasoning behind a certain restoration principle. In result, I now take part in the evaluation process when beginning a new project. For students who may face a similar situation, my advice would be not to feel afraid to ask questions or start a conversation! In my case, the team became excited to teach me more when they saw, through the questions I was asking, my interest and curiosity in art restoration.

Sitting for long periods of time meticulously trimming washi paper and preparing starch paste in a large wooden vat becomes taxing on the shoulders and eyes, but I have discovered that I can refocus my attention through conversation. Oftentimes I become so accustomed to speaking casually in conversation that when it comes to expressing gratitude, I carelessly neglect social etiquette and forget to attach the formal “gozaimasu” to my informal “arigatou”. I am corrected instantly, and my honest mistake reinforces the importance of maintaining a formal student-teacher relationship when dealing with work-related matters. However, I was told that if “arigatou gozaimasu” is too long, I could always opt for the Kansai-equivalent, “ookini”. Apparently, if used towards a Kansai-native, “ookini” carries the same formal weight as “gozaimasu”. I have yet to try it out.

As the semester is reaching its end, I still feel that there is a lot I could improve in terms of restoration. At least once or twice per week, I make a careless mistake in my work, leading Nakamura-san to address me by “onesan”, which translates to “older sister”. Since I am the youngest of the group, I was initially confused as to why I was being called “onesan”. However, seeing that I am only called this when I overlook a mistake, perhaps it is an indirect message that I should to be more careful next time. Nevertheless, I feel respected in my position, and while I rarely receive any direct compliments from Nakamura-san, I can sense through her patience that she is silently supporting me in both my language and restoration endeavors.

With that said, I would like to thank KCJS for giving students the opportunity to step out into the Kyoto community through CIP, as well as ARC for taking care of me throughout this year. This experience is one I will continue to carry with me as I continue my studies in Japanese and art restoration.

Ookini!