今貂子先生の舞踏ワークショップに参加しています。私はパフォーマンアートに興味があります。専門がパフォーマンアートの友達の勧めめで、舞踏が習いたくなりました。舞踏は日本の現代的なダンスで、 裸体の上から全身白塗をするとか、腰を低く曲げるなどの特徴があります。舞踏は人類の身体にたいする、意識を高めるためのダンスで、私の専門は脳科学ですので、身体に対する意識に興味もあるし、ダンスはいい運動だと思うし、今貂子先生の舞踏ワークショップを参加し始めました。

毎週の木曜日、午後七時から、九時まで、九条付近のスタジオで踊ります。ワークショップは、日本人もいれば、アメリカ人もいて、ドイツ人もいれば、フランス人もいるというように国際的な雰囲気があります。ワークショップの前に、皆一緒に雑巾で拭き掃除します。また、ワークショップの後で、よく先生とプロダンサーと他の学生と一緒にお茶を飲んで、例えば、舞踏の身体論と最近の演劇など、色々なことを話します。今貂子先生はいつも優しいし、自分の研究に対して謙虚です。

舞踏ワークショップでは、まず呼吸練習と基本の身体の準備運動を一時間します。そして、簡単な舞踏の姿勢を習って、即興でおどります。最後に、ほぐす運動をして、お稽古が終わります。今まで、舞踏のワークショップ四回参加しました。面白かったです。身体に対する意識はまだ分かりませんが、先週、情報科学芸術大学の小林先生が今貂子先生に依頼に応えて、舞踏の歴史と身体論についてレクチャーをしてくださいました。舞踏の哲学がよく分かりました。

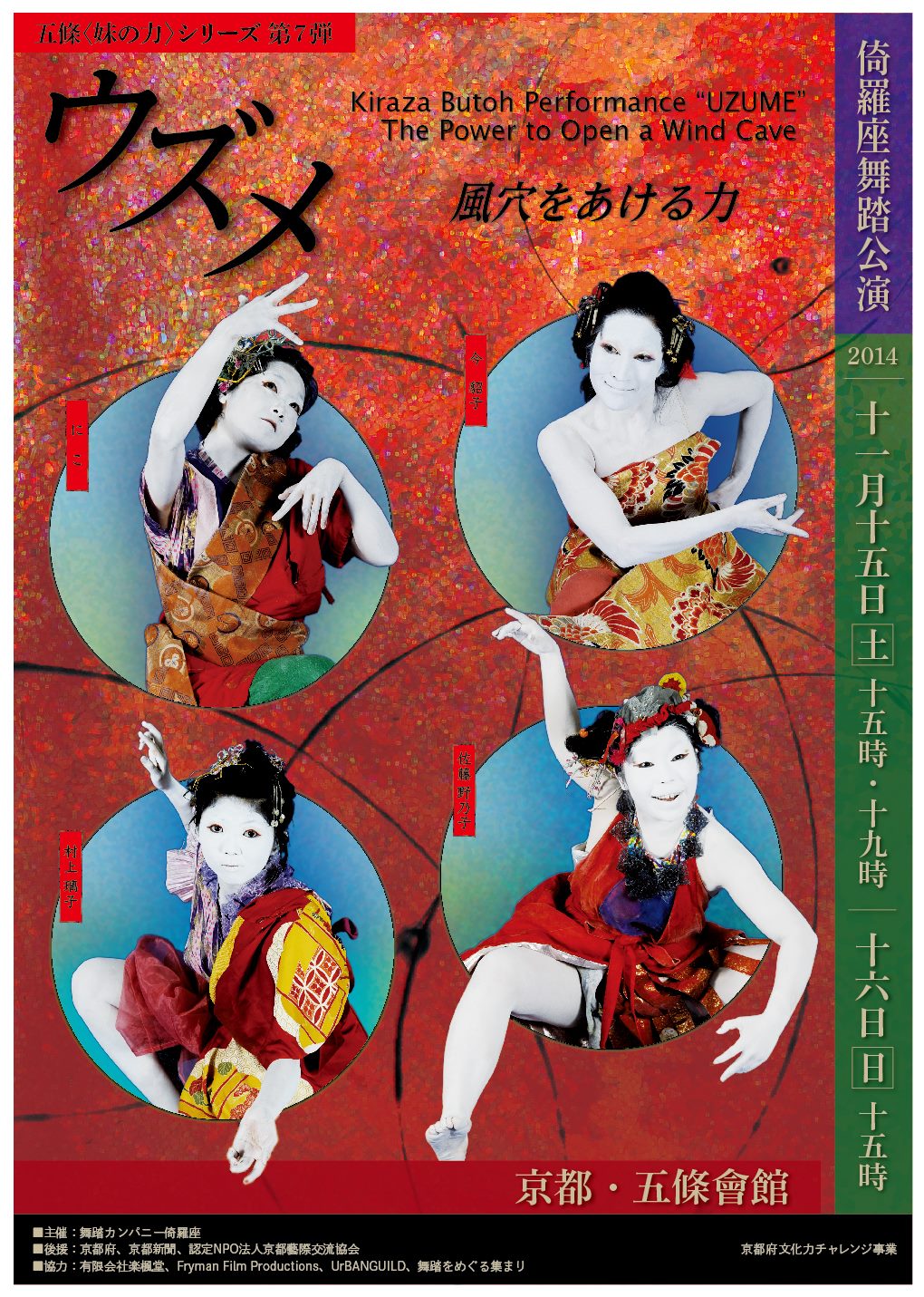

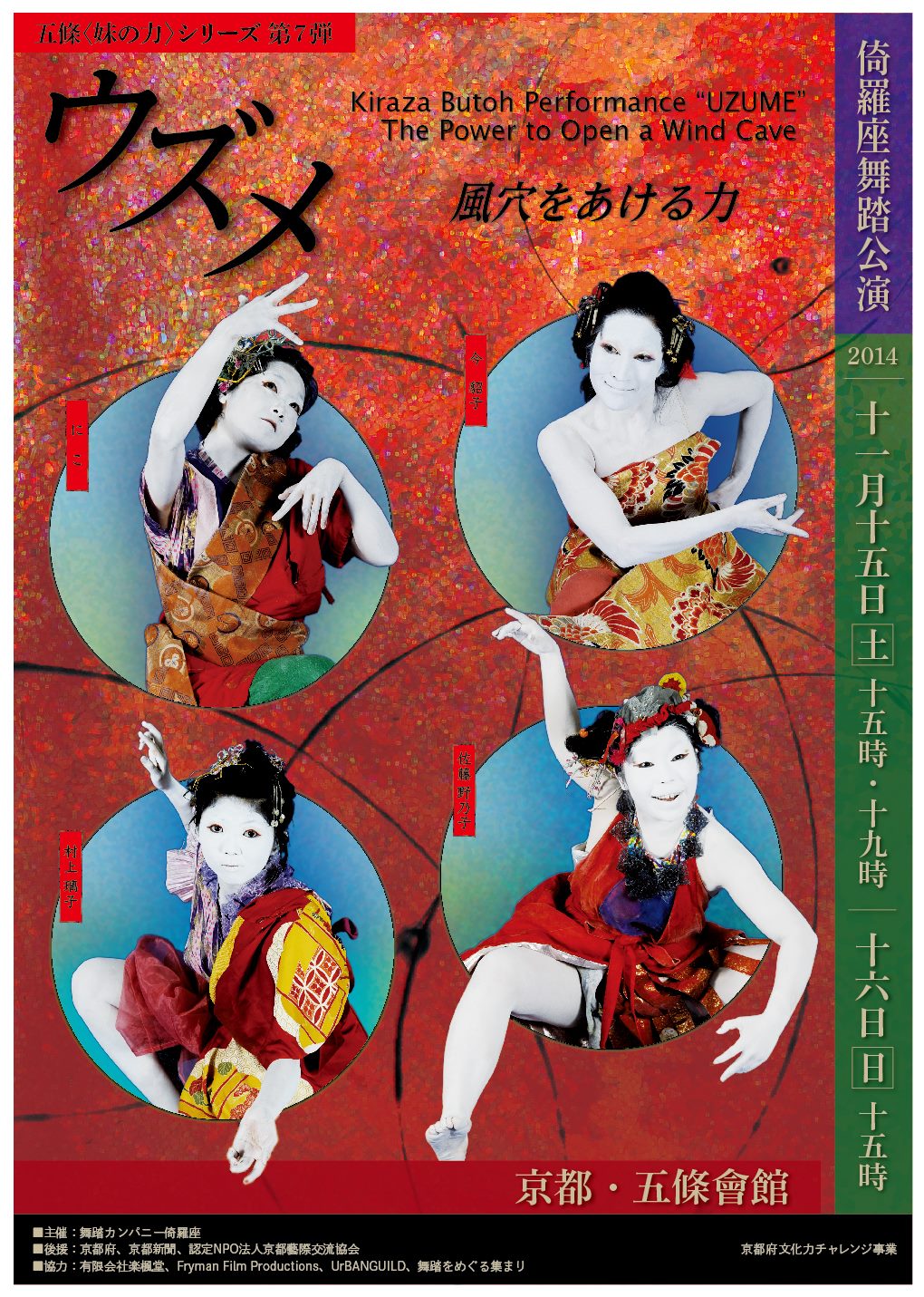

引き続き楽しみにお稽古を続けます。先生の公演11月15日と11月16日です。皆さん、時間があれば、ぜひ、いらしてください。